Separating Signal From Noise in UAP Research

The Bureau Bulletin By Melissa Madrigal

February 2026

Public interest in unidentified anomalous phenomena has accelerated rapidly in recent years. With that surge has come an equally rapid increase in material such as videos circulating online, eyewitness accounts shared across platforms, sensor readings quoted secondhand, and interpretations layered on top of one another. The influx can create the impression that progress is being made simply because more information is available. In reality, the opposite is often true. One of the challenges in UAP research today is not lack of data, but discernment, knowing how to distinguish meaningful signal from the noise that surrounds it.

In research, “signal” does not mean something extraordinary or unexplained. It refers to data that can be examined in context, constrained by known variables, and compared against established reference points. Noise, by contrast, is not necessarily false or dishonest. It often consists of interpretation without sufficient anchors, incomplete information treated as conclusive, or observations removed from the conditions that produced them. When noise dominates, even sincere inquiry can drift away from clarity rather than toward it.

Conclusions are only as stable as the foundation beneath them. This distinction matters because in many fields, especially those dealing with rare or poorly understood phenomena, the temptation is to move quickly from observation to explanation. But responsible investigation works in the opposite direction. It begins by asking what can be verified, what can be ruled out, and what remains genuinely unknown. Progress often looks like careful elimination.

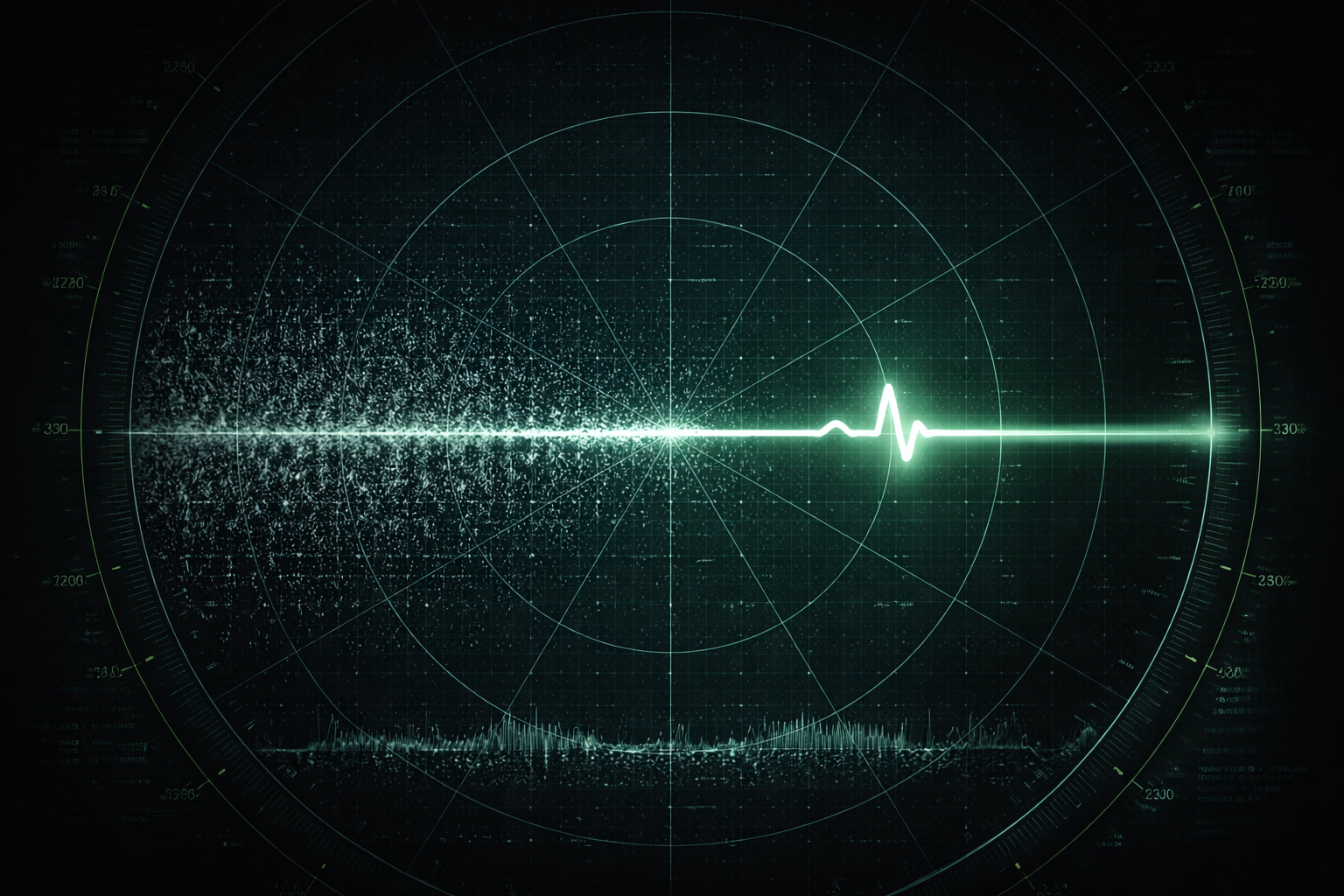

Consider visual data. Images and videos are frequently treated as obvious, yet they are among the most context dependent forms of evidence. Camera type, lens characteristics, compression artifacts, lighting conditions, motion relative to the sensor, and environmental interference all shape what is recorded. Without that context, interpretation fills the gaps. What appears anomalous may simply be underspecified. The signal is not the image alone, it’s the conditions under which it was produced and evaluated.

The same principle applies to eyewitness accounts. Human perception is not a recording device. It is influenced by stress, expectation, prior knowledge, and environmental conditions. This does not invalidate an eyewitness’s testimony, but it does define its limits. In research, eyewitness reports function as prompts for further inquiry, not as standalone proof. Treating them otherwise shifts attention away from investigation and toward belief.

In research settings, I’ve found that one persistent challenge is the collapse of uncertainty into narrative. When gaps in data are filled prematurely, the result may feel satisfying, but it weakens the overall integrity of the work. Uncertainty is often mistaken for a lack of knowledge. In reality, it is a boundary marker, a way of identifying where evidence ends and speculation begins. Keeping that boundary doesn’t stop progress, it makes it more reliable and is essential to credibility.

Separating signal from noise also means knowing how errors affect what we see. Every measurement system has limitations. Sensors can misread, instruments can saturate, and environmental factors can introduce distortions. Recognizing these constraints does not diminish the value of data but clarifies it. Claims that cannot survive basic questions about measurement, consistency, or alternative explanations do not become stronger through repetition. They become louder, not clearer.

Curiosity and exploration matter, but discipline is what keeps them grounded. Serious research does not advance by endorsing every anomaly or by dismissing them reflexively. It advances by applying consistent standards, even when doing so leads to inconclusive results. When clear answers are rare, how evidence is handled matters more than conclusions.

As public discussion around UAP continues to evolve, the distinction between signal and noise will only grow more important. Interest alone doesn’t lead to understanding. That comes from restraint, transparency about limits, and being willing to say ‘we don’t know yet’ when the data supports it. Clarity, not certainty, is the foundation of credible research.

Before asking what anomalous phenomena may ultimately represent, it is worth being clear about how evidence is weighed, how claims are evaluated, and why careful separation between what is measurable and what is inferred, is not a barrier to discovery, but a prerequisite for it.

###

Melissa Madrigal is the Director of Research for the International UFO Bureau (IUFOB), where she leads advanced investigations into electromagnetic signal patterns and harmonic fields associated with unidentified aerial phenomena.

To Contact Melissa: